One of the biggest problems faced by children and adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is the difficulty in spontaneously initiating and acquiring communication functions. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurological and developmental disorder that affects how people interact with others, communicate, learn, and behave. Although autism can be diagnosed at any age, it is described as a “developmental disorder” because symptoms generally appear in the first two years of life. Therefore, it is important that their communication partners recognise and respond appropriately to the child’s attempts to communicate, regardless of the form in which they are presented. In this way the child learns to influence their environment and thus expands the functions of communication (Stošić, 2013).

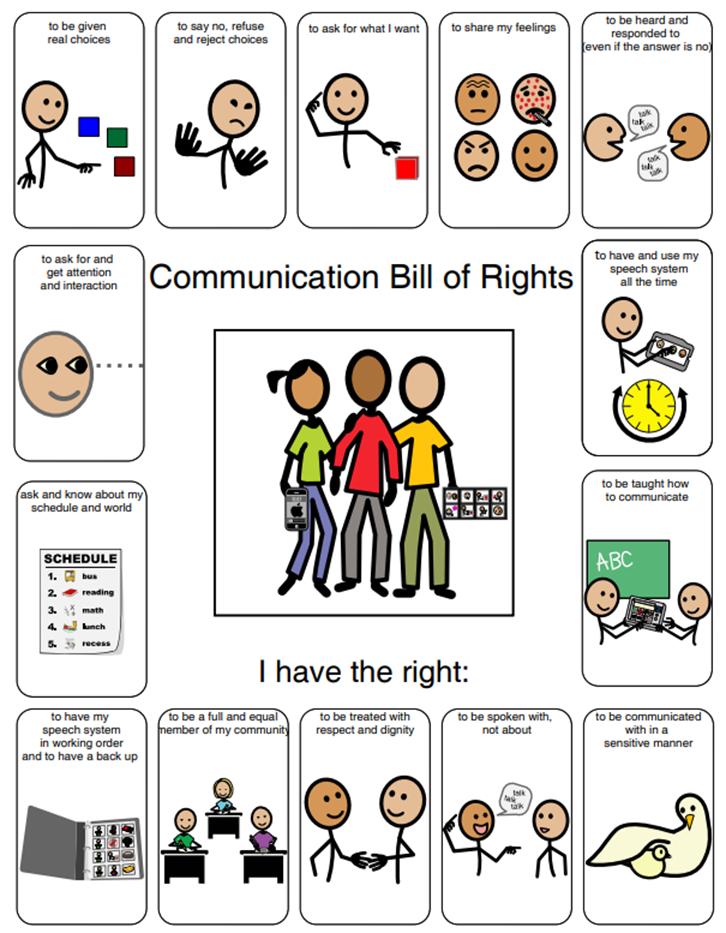

Improving functional communication skills increases independence in activities of daily living (Drager et al., 2010), which is why it is necessary to work on long-term goals that include communication autonomy, accessibility and competence (Porter and Cafiero, 2009). It is important to emphasise that people with ASD do not only have difficulties in creating a communication response, but also have certain problems in processing, or understanding, communication inputs (understanding verbal instructions) (Cafiero, 2001).

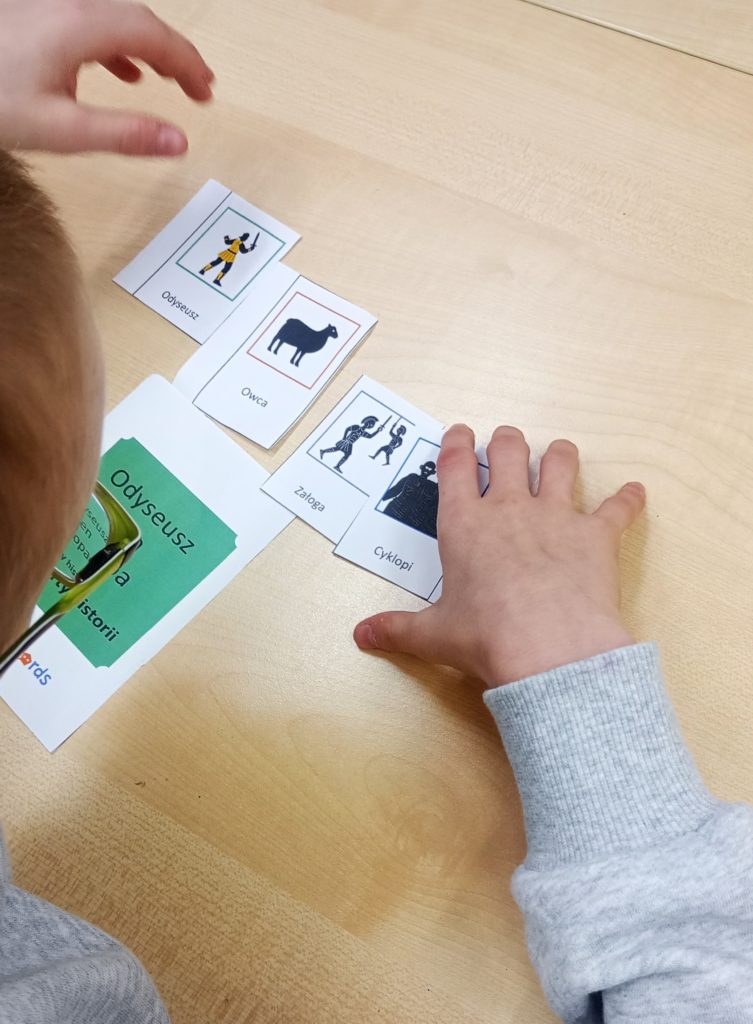

In order to enable children with ASD to have as much independence as possible and participate equally in society, we must find a way to make it easier for each child to understand communication messages and express themselves, and as stated by Mirenda (2003), research has shown that many children and adults with ASD, regardless of the level of difficulty, can successfully use alternative techniques for functional communication if they are provided with appropriate instructions and learning opportunities.

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) provides a means of effective communication to individuals with autism spectrum disorder, many of whom are unable to use conventional speech effectively. Research has produced more support for aided AAC than sign language for people with ASD, although a few studies have conclusively demonstrated the effectiveness of sign language. Literature has addressed the use of sign language with people with ASD since the 1970s (Ganz & Gilliland, 2014).

The number of adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the world is growing (Gerhardt & Lainer, 2011). Unfortunately, the number of opportunities for these individuals to participate successfully in the world is limited and, as a result, they often experience poor outcomes in adulthood relative to their roles in the vocational, community, and social sectors.

Using a system that is appropriate for a child or person with disabilities and their environment increases independence, expression, learning and social inclusion. This can have a positive impact on reducing undesirable and socially unacceptable behaviours, developing self-esteem and generally leading to an improvement in the quality of life”. Also, in the long term, they can significantly reduce costs if applied from childhood because they enable better education and thus increase the likelihood of employment and better jobs later in life.

It should also be emphasised that AAC presents various advantages to acquire and reproduce new knowledge. Consequently, we should also emphasise that its application is essential for people with ASD’s education and daily life. (Bašić, Maćešić Petrović, Zdravković, Kovačević, Gajić and Arsić, 2020).

AAC systems for people with autism spectrum disorder include high-tech devices such as various electronic devices, tablets, communicators, and speech-generating devices, and low-tech devices, such as pictures or symbols that can be attached to a communication board or exchanged with a communication partner (Bondy and Frost 2002, cited in Lang et al., 2014).

AAC not only benefits children with developmental disabilities and people with disabilities who, by using it, are able to participate in everyday and school activities; it also significantly contributes to their caregivers, preschool and school staff by reducing the time spent providing personal assistance and thus increasing the time available for other activities. The benefits extend even to the wider community; with the help of AAC, people can participate in the society and therefore contribute to the environment and are less reliant on government assistance (Berry and Ignash, 2003) .

Literature

Bašić, A., Maćešić-Petrović, D., Zdravković, R., Kovačević, J., Gajić, A., & Arsić, B. (2020). Upotreba asistivne tehnologije u službi sticanja znanja kod osoba sa poremećajima iz spektra autizma. U: Vladimir Katić (Ur.): XXVI Skup trendovi razvoja:“inovacije u modernom obrazovanju”, 242-245

Berry B.E., Ignash S. (2003). Assistive technology: providing independence for individuals with disabilities. Rehabil Nurs. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2003.tb01715.x

Cafiero, J. M. (2001). The Effect of an Augmentative Communication Intervention on the Communication, Behavior, and Academic Program of an Adolescent with Autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 16(3), 179-189.

Ganz, J. B. (2015). AAC Interventions for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders: State of the Science and Future Research Directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31(3), 203–214. doi:10.3109/07434618.2015.1047532

Gerhardt, Peter F., Lainer I. (2010). Addressing the Needs of Adolescents and Adults with Autism: A Crisis on the Horizon. DOI: 10.1007/s10879-010-9160-2

Holyfield, C., Drager, K. D. R., Kremkow, J. M. D., & Light, J. (2017). Systematic review of AAC intervention research for adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 33(4), 201–212. doi:10.1080/07434618.2017.1370495

Stošić, J. (2013). Spontana komunikacija i njena učinkovitost u djece s poremećajem iz autističnog spektra. Hrvatska revija za rehabilitacijska istraživanja, Vol 49, 115-129.